This story by Saadat Hasan Manto is said to be the most powerful satire on the Idea of Partition of India and Pakistan. BBC has included it in its 100 stories that shaped our world. along with legends like Shakespeare, Kafka and Virginia Woolf.

“A classic short story that translates the trauma of partition through the exchange of lunatics across the India and Pakistan border.”

BBC

The Mental Asylum of Lahore

The order came in 1950, 3 years after the partition of Pakistan and India. It has come right from the top.

After a lot of meetings by the leaders at the highest position, after all the blood had been shed, houses had been burnt, wives had lost their husbands and family had been orphaned, the leaders have come to a conclusion that the partition of Pakistan and India is complete, except one.

In the mental asylum of Lahore, there still remained few hindu and sikh lunatics. All of their relations have left Pakistan for India. No-one is available to take their responsibility. Hence they should be deported to India.

No-one had taken the opinion of the inmates of the asylum. But the inmates were stirred. Of course a lunatic can not and should not have any opinion. But all inmates were not mad. Some of them were murderers. Their relatives had bribed the authority to get them admitted to this asylum. This became a hotly discussed topic among the inmates.

They all were in India only few days ago. How come they all moved to Pakistan without boarding a train. Sialkot used to be in Hindustan, but now it was said to be in Pakistan. Who knew whether Lahore, which now is in Pakistan, tomorrow might go off to Hindustan? And who could place his hand on his chest and say whether Hindustan and Pakistan might not both someday vanish entirely?

There were two Anglo-Indians in the European ward. When they heard that the British were leaving, they were stirred. They thought and thought.. what could happen to them now ? Would they get bread in breakfast or had to do with dal, roti ? This partition can change their breakfast they thought.

They thought and thought and then stopped thinking. Of course, lunatics are not supposed to have any opinion. The court thinks so. Judges also think so.

Except one. His name was Bishan Singh. He had been in this mental asylum for fifteen years. Throughout these fifteen years, he hadn’t slept even for a moment. He didn’t even lie down. Sometimes though, he would lean against a wall and muttered an oath. “Upar di gur gur di annex di be dhyana di mung di daal of the lantern.” But nobody could understand what he meant though he would repeat it several times in a day. His feet swelled up because of the constant standing. His ankles were swollen too. But despite this bodily discomfort, he didn’t lie down and rest. He rarely bathed, the hair of his beard and head had clumped together, which gave him a very frightening appearance. But the man was harmless.

In fifteen years, he’d never quarrelled with anybody. Some of the longtime custodians of the asylum knew that he had some lands in Toba Tek Singh. He was a prosperous landlord, when suddenly his mind gave way. His relatives bound him in heavy iron chains, brought him to the asylum, got him admitted, and left.

Sometimes his relatives from Lahore would visit him. He had an infant daughter also. Bishan Singh didn’t recognize her. The girl wept when she saw her father. Lately she had grown up to be a beautiful young girl in these 15 years and would weep when she saw her father. Since the partition, even these visitors didn’t come any more. Though insane, still he missed those visitors. How strange ? Bishan Singh was sure, these kind visitors were coming from the lands of Toba Tek Singh. Probably like Sialkot, his lands at Toba Tek Singh had also moved.

There was an inmate in the mental asylum, who called himself God. Bisham Singh asked him whether Toba Tek Singh was in Pakistan or Hindustan. He burst out laughing and said, “It’s neither in Pakistan nor in Hindustan– because we haven’t given the order yet.”

Since then Bishan Singh regularly pleaded and cajoled to this god to pass the order so that his kind visitors may come to him again. but the inmate God said he was very busy, he had countless orders to give.

So one day Bishan Singh burst out at him, “Upar di gur gur di annex di be dhyana di mung di dal di Guruji da Khalsa and Guruji ki fateh.

Though no body could understand him, perhaps he said, “You don’t answer my prayer because you are the God of the Muslims! If you were the God of the Sikhs, you’d surely have listened to me!”

Fazal Din comes to meet

Some days before the exchange, a Muslim from Toba Tek Singh came to visit him. The guards told him,”He’s come to visit you. He’s your friend Fazal Din.” Bishan Singh didn’t move.

Fazal Din said, “All your family are well; they’ve gone off to Hindustan.” Bishan Singh turned to go back. “Your daughter Rup Kaur also went off with them.”

At this Bishan Singh stopped and asked,” Daughter Rup Kaur…”

“Yes, she was fine. They told me to check on your welfare from time to time…. Now I’ve heard that you’re going to Hindustan…. Give my greetings….. And… and if there’s anything I can do for you, tell me; I’m at your service….”

Bishan Singh asked Fazal Din, “Where is Toba Tek Singh?”

Fazal Din said with some astonishment, “Where is it? Right there where it was!”

Bishan Singh asked, “Is it in Pakistan, or is it moved to Hindustan?”

Fazal Din didn’t know. Without saying another word, Bishan Singh walked away muttering his oath “Upar di gur gur di annex di be dhyana di mung di dal

At the Wagha Border

On an extremely cold day, lorries full of Hindu and Sikh lunatics from the Lahore mental asylum set out for the Wagha border. At the border the two nations’ superintendents met each other; and after the routine procedures, the exchange began, and went on all night. None of the lunatics were in favor of this exchange. They couldn’t understand why they were being uprooted from their place and thrown away like this. Some refused to emerge out of the lorry. Those who were willing to come out suddenly ran here and there. If clothes were put on the naked ones, they tore them off their bodies and flung them away.

As always, Bishan Singh remained quiet all the time muttering his oath. When his turn came, the officer from the Indian side began to enter his name in the register.

Bishan Singh asked, “Where is Toba Tek Singh? In Pakistan, or in Hindustan?”

The accompanying officer laughed: “In Pakistan.”

On hearing this, Bishan Singh leaped up, dodged to one side, and ran to rejoin his companions at the Pakistan side. The Pakistani guards seized him and began to pull him in the other direction, but he refused to move.

“Toba Tek Singh is here!” — and he began to shriek with great force, “Upar di gur gur di annex di be dhyana di mung di dal of Toba Tek Singh and Pakistan!“

They tried hard to persuade him: “Look, now Toba Tek Singh has gone off to Hindustan! And if it hasn’t gone, then it will be sent there at once.”

But he didn’t believe them.

When they tried to drag him to the Indian side by force, he stopped in the middle and stood there on his swollen legs as if now no power could move him from that place.

Since the man was harmless, no further force was used on him. He was allowed to remain standing there, and the rest of the work of the exchange went on.

…

In the pre-dawn peace and quiet, Bishan Singh let out a shriek that pierced the sky…. From here and there a number of officers came running, and they saw that the man who for fifteen years, day and night, had constantly stayed on his feet, lay prostrate on the ground.

On one side there, behind barbed wire, was Hindustan. On the other side, behind the same kind of wire, was Pakistan. In between, on that piece of ground that had no name, lay Toba Tek Singh.

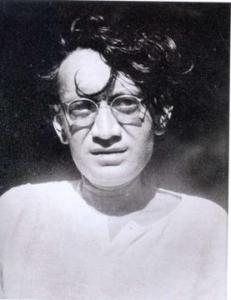

Saadat Hasan Manto was born in Ludhiana and schooled in Amritsar and AMU. In 1948 he migrated to Pakistan. In the islamised nation of Pakistan, sessions judge ruled that he would be sent to jail if he continued to write provocative stories. He stopped writing, sank into depression and was admitted to the mental Asylum at Lahore. He died in 1955